Solutions ∨

Learning and Performance → ∨

Mandatory TrainingIssue required courses and monitor compliance ∨

Continuing EducationOffer clinicians training to meet license requirements ∨

Professional DevelopmentEngage staff and empower career growth ∨

Clinical DevelopmentEnhance skills with clinician-built content ∨

Certification ReviewBuild knowledge and increase exam pass rates ∨

Competency ManagementMeasure and evaluate knowledge, skills, and abilities ∨

Obstetrics SolutionReduce variation in care with data-driven learning ∨

Onboarding SolutionTailor nurse training and reduce turnover ∨

Recruiting and Staffing → ∨

Talent Acquisition AdvertisingTarget your recruitment to our 3M+ nurse community ∨

Validated AssessmentsGauge job fit with clinical, behavioral, situational assessments ∨

Nurse Job BoardPost your nurse opportunities on Nurse.com ∨

Compliance Management → ∨

Compliance SoftwareMeet requirements with easy to administer package ∨

Mandatory TrainingIssue required courses and monitor compliance ∨

View All Solutions → ∨

Who We Serve ∨

Who We Serve → ∨

Hospitals and Health SystemsLarge multisite systems, critical-access hospitals, staffing agencies ∨

Individual Healthcare WorkersPhysicians, nurses, clinicians, and allied health professionals ∨

Post-Acute and Long-Term CareSkilled nursing facilities, continuing care retirement communities and life plan communities, assisted living facilities, rehab therapy providers, and hospice agencies ∨

Behavioral and Community HealthBehavioral health, intellectual and developmental disabilities, applied behavior analysis, community health centers, and children, youth, and family-serving organizations ∨

Home Health and Home CareHome health and home care agencies and organizations ∨

Government OrganizationsFederal, state, and local entities ∨

Case Studies ∨

PAM Health Supports Business Growth, Employee Engagement, and Better Patient Outcomes With ReliasPAM Health utilized Relias to make post-acquisition employee onboarding easier and to influence positive patient outcomes through high-quality staff training and coaching. ∨

CSIG Depends on the Relias Platform Through Change and GrowthBefore 2020, Common Sail Investment Group (CSIG) conducted all its senior living staff training and education in person in different locations. ∨

Why Relias ∨

Why Relias → ∨

TechnologyEngage learners and ease burden for administrators ∨

Measurable OutcomesImprove workforce, organization, and patient results ∨

ServicesReduce administrative burden with professional solutions ∨

Expert ContentTrust Relias for quality, award-winning courses and tools ∨

CommunityTap into clinician resources and peer support ∨

Resources → ∨

How Mental Health and Social Determinants Are Driving Maternal MortalityThe CDC has uncovered another dimension affecting the already alarming problem of maternal mortality in the U.S… ∨

2023 DSP Survey ReportThe 2023 DSP Survey Report highlights feedback from 763 direct support professionals (DSPs) across the country on job satisfaction, supervision… ∨

Resources ∨

Resource Center → ∨

BlogKeep up with industry trends and insights ∨

Articles and ReportsReview recently published thought leadership ∨

Success StoriesRead about Relias clients improving outcomes ∨

EventsFind Relias at an upcoming industry conference ∨

WebinarsRegister for upcoming key topic discussions ∨

SupportContact us for help with your account ∨

PodcastExplore conversations with healthcare experts ∨

Upcoming Event ∨

Contact Sales → ∨

Company ∨

About Relias → ∨

CareersView our open positions ∨

MediaReview our latest news and make press inquiries ∨

EventsFind Relias at an upcoming industry conference ∨

Alliances and PartnershipsScan our industry connections and relationships ∨

AwardsCheck out our latest recognitions ∨

DiversityLearn more about Relias’ commitment to DEIB ∨

In the News → ∨

Log In ∨

Login Portals ∨

Relias Learning ∨

Nurse.com ∨

Relias Academy ∨

Wound Care Education Institute ∨

FreeCME ∨

Relias Media ∨

Solutions ∨

Learning and Performance → ∨

Mandatory TrainingIssue required courses and monitor compliance ∨

Continuing EducationOffer clinicians training to meet license requirements ∨

Professional DevelopmentEngage staff and empower career growth ∨

Clinical DevelopmentEnhance skills with clinician-built content ∨

Certification ReviewBuild knowledge and increase exam pass rates ∨

Competency ManagementMeasure and evaluate knowledge, skills, and abilities ∨

Obstetrics SolutionReduce variation in care with data-driven learning ∨

Onboarding SolutionTailor nurse training and reduce turnover ∨

Recruiting and Staffing → ∨

Talent Acquisition AdvertisingTarget your recruitment to our 3M+ nurse community ∨

Validated AssessmentsGauge job fit with clinical, behavioral, situational assessments ∨

Nurse Job BoardPost your nurse opportunities on Nurse.com ∨

Compliance Management → ∨

Compliance SoftwareMeet requirements with easy to administer package ∨

Mandatory TrainingIssue required courses and monitor compliance ∨

View All Solutions → ∨

Who We Serve ∨

Who We Serve → ∨

Hospitals and Health SystemsLarge multisite systems, critical-access hospitals, staffing agencies ∨

Individual Healthcare WorkersPhysicians, nurses, clinicians, and allied health professionals ∨

Post-Acute and Long-Term CareSkilled nursing facilities, continuing care retirement communities and life plan communities, assisted living facilities, rehab therapy providers, and hospice agencies ∨

Behavioral and Community HealthBehavioral health, intellectual and developmental disabilities, applied behavior analysis, community health centers, and children, youth, and family-serving organizations ∨

Home Health and Home CareHome health and home care agencies and organizations ∨

Government OrganizationsFederal, state, and local entities ∨

Case Studies ∨

PAM Health Supports Business Growth, Employee Engagement, and Better Patient Outcomes With ReliasPAM Health utilized Relias to make post-acquisition employee onboarding easier and to influence positive patient outcomes through high-quality staff training and coaching. ∨

CSIG Depends on the Relias Platform Through Change and GrowthBefore 2020, Common Sail Investment Group (CSIG) conducted all its senior living staff training and education in person in different locations. ∨

Why Relias ∨

Why Relias → ∨

TechnologyEngage learners and ease burden for administrators ∨

Measurable OutcomesImprove workforce, organization, and patient results ∨

ServicesReduce administrative burden with professional solutions ∨

Expert ContentTrust Relias for quality, award-winning courses and tools ∨

CommunityTap into clinician resources and peer support ∨

Resources → ∨

How Mental Health and Social Determinants Are Driving Maternal MortalityThe CDC has uncovered another dimension affecting the already alarming problem of maternal mortality in the U.S… ∨

2023 DSP Survey ReportThe 2023 DSP Survey Report highlights feedback from 763 direct support professionals (DSPs) across the country on job satisfaction, supervision… ∨

Resources ∨

Resource Center → ∨

BlogKeep up with industry trends and insights ∨

Articles and ReportsReview recently published thought leadership ∨

Success StoriesRead about Relias clients improving outcomes ∨

EventsFind Relias at an upcoming industry conference ∨

WebinarsRegister for upcoming key topic discussions ∨

SupportContact us for help with your account ∨

PodcastExplore conversations with healthcare experts ∨

Upcoming Event ∨

Contact Sales → ∨

Company ∨

About Relias → ∨

CareersView our open positions ∨

MediaReview our latest news and make press inquiries ∨

EventsFind Relias at an upcoming industry conference ∨

Alliances and PartnershipsScan our industry connections and relationships ∨

AwardsCheck out our latest recognitions ∨

DiversityLearn more about Relias’ commitment to DEIB ∨

In the News → ∨

Learning Management and TrainingResearch StudiesThe Impacts of Scenario-based Online Training and Retrieval-based Learning on Health Care Professionals’ ability to Identify HIPAA Violations in Social Media.

Background

Retrieval is defined as getting and bringing something back1. Studies consistently show that retrieving knowledge subsequent to obtaining that knowledge improves learning and retention2-3. Information retrieval presented at intervals over time, or “spaced repetition,” should be delayed after the initial learning, making the information less accessible in one’s memory than if the review were immediately after learning4-5. The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) included national standards for protecting patient health information privacy6. According to HIPAA, any communications regarding personally identifiable patient information must be secure and transmitted only to permissible parties. Social media communications create abundant possibilities for the improper sharing of personal health care information, putting both the patient privacy and health care organization compliance at risk7.

Methods

We conducted a randomized (by organization) controlled trial examining the impact of spaced learning on healthcare professionals’ retention of an online training on HIPAA and social media use. Fifty-seven learners from four community health organizations completed a pre-assessment, an online training course, a post-assessment, and a 90-day follow-up assessment. The online training course consisted of a 30-minute course titled, “HIPAA Do’s and Don’ts: Electronic Communication and Social Media,” that taught learners to identify actions on social media that could result in a HIPAA breach. The three assessments took about 10 minutes each and collected demographic, attitude, social media use, and knowledge data. The knowledge questions included both general and scenario-based questions and the attitude questions focused on confidence levels in identifying HIPAA violations and motivation levels for learning about the topic. Learners (n=20) from two of the four organizations were sent six retention questions via email over a two-month period after taking the online training. Learners (n=37) from the other two organizations did not receive retention questions in the two months following the training.

Results

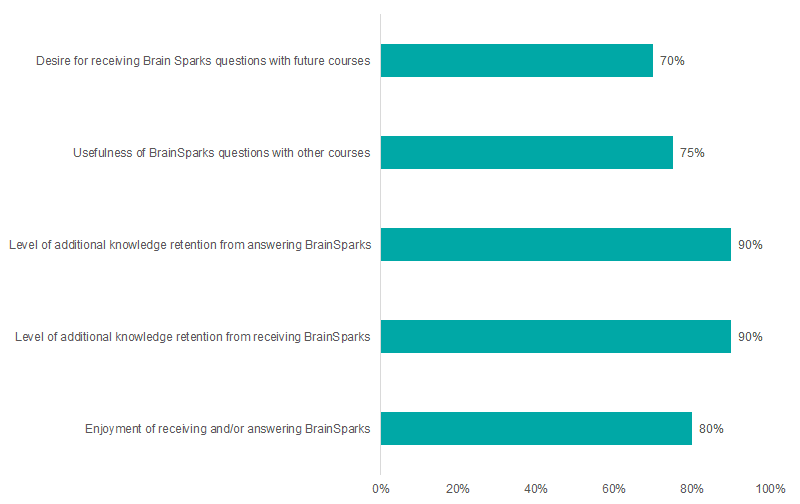

On average, across all learners, knowledge about HIPAA and social media increased significantly from pre-assessment to post-assessment, but was not sustained at 90-day follow-up. There was no significant difference in knowledge retention at follow-up between the retention question intervention group and the control group. Most learners reported they enjoyed receiving retention questions, believed they gained knowledge retention from the questions, and desire follow-up retention questions with future online training courses.

Figure 1: Social Validity Survey Responses

Discussion

Although participants that completed Brain Sparks reported that they enjoyed them, the version of Brain Sparks 1.0 did not significantly retain knowledge over time. Six questions delivered over the period of two months may not help maintain knowledge retention. Learners may remain confident in their knowledge in the few months after an online training despite not maintaining the immediate knowledge gained from the training. This increased confidence level is of concern for professionals in healthcare and other disciplines who may erroneously believe they know and understand important concepts without questioning themselves or seeking the additional training they need. We recommend further research to determine effective spaced repetition strategies to help ensure learners maintain the knowledge they gain through online training. Relias is currently looking at creating Brain Sparks 2.0 to address these findings.

Read More

An article in Training magazine discusses this study and the importance of training for memory retention.

References

- Retrieve [Def. 1]. (n.d.) In Oxford Dictionaries Online, Retrieved July 26, 2016, from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/us/definition/american_english/retrieve.

- Karpicke, J. D., & Grimaldi, P. J. (2012). Retrieval-based learning: A perspective for enhancing meaningful learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 401-418.

- Carpenter, S. K., Cedpeda, N. J., Rohrer, D., Kang, S. H. K., & Pashler, H. (2012). Using spacing to Enhance Diverse Forms of Learning: Review of Recent Research and Implications for Instruction. Educational Psychology Review, 24(3), 369-378.

- Brown, P. C., Roediger, H. L., & McDaniel, M. A. (2014). Make it stick. Harvard University Press.

- Karpicke, J. D., & Roediger III, H. L. (2007). Expanding retrieval practice promotes short-term retention, but equally spaced retrieval enhances long-term retention. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 33(4), 704.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. Retrieved July 26, 2017, from https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-professionals/index.html

- Cain, J. (2011). Social media in health care: the case for organizational policy and employee education. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 68(11), 1036.

Read more about this research

Author

M. Courtney Hughes PhD, MS

Senior Researcher, Relias

Publication

Training Magazine June 2018

Research Partner

One Hope United; Lutheran Child and Family Services

Related Resources

Research Studies

Health Behaviors and Related Disparities of Insured Adults with a Health Care Provider in the United States, 2015–2016

Using the 2015 and 2016 CDC’s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, we examine the prevalence of health behaviors and the existence of disparities in...

Research Studies

Evaluating Learner Motivation, Engagement and Retention

This study examined the impact of story-based back injury prevention video training on learner motivation, engagement, and knowledge...

Research Studies

Evaluation of an Employee Wellness Training Series

This study examines the knowledge and health behavior outcomes associated with an educational series of mobile-friendly, micro-learning wellness courses...