There are certainly some less-than-ideal stories that both patients and providers could share around childhood obesity. From the nine-year-old whose primary care provider told him (in his recollection) that he was going to get diabetes and die to the 17-year-old who walked away thinking that being in the 99th percentile for BMI was fine, it is clear that obesity is a tough topic for all involved.

Childhood obesity is not an uncommon topic though — according to the American Heart Association:

- 1-in-3 children and adolescents, ages 2-19 are overweight or obese.

- The cost of obesity in the United States is ~$147 billion.

- Nearly ½ of preschool-aged children do not get enough physical activity.

With this in mind, it is imperative that providers become adept at discussing not just the risk factors and consequences with their patient populations, but a path forward towards better health.

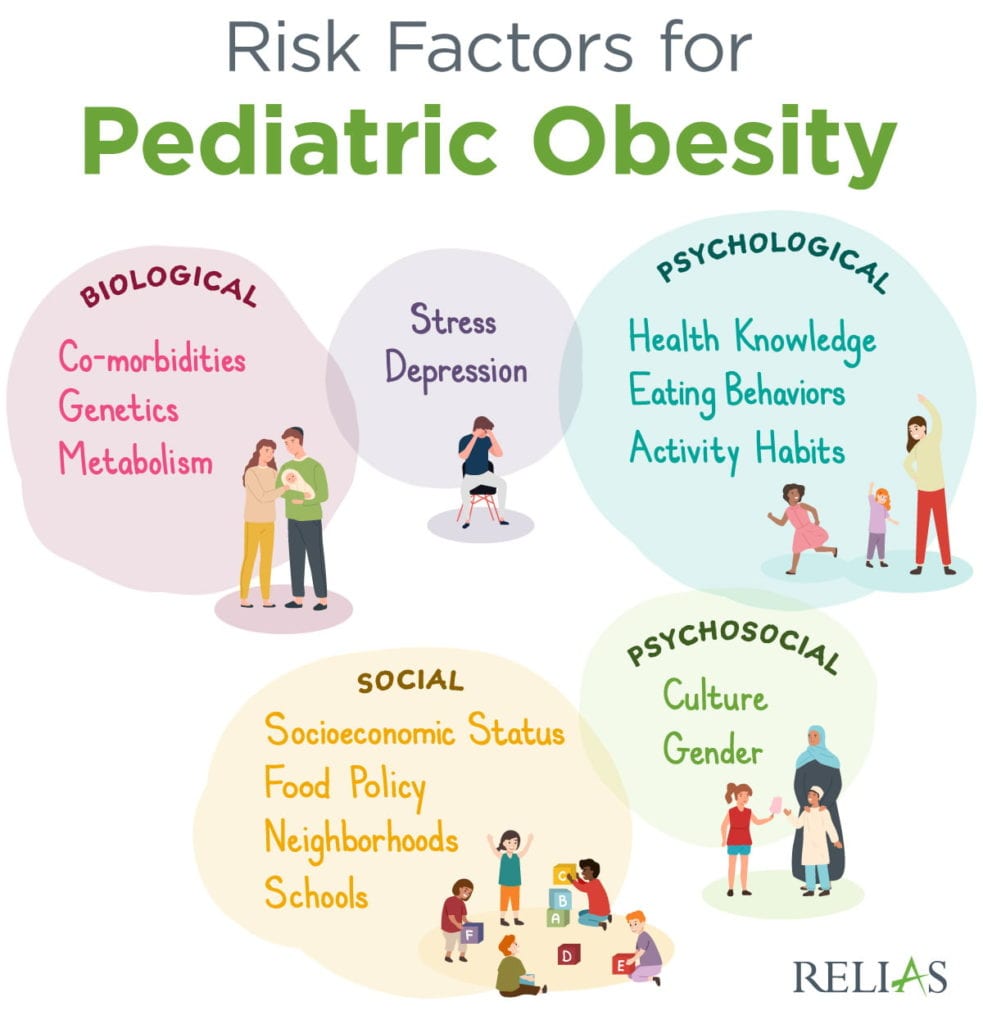

There are a few key pieces to address in creating this path to better health habits, including the misconception that childhood obesity is the result of a metabolic disorder. One study found, for example, that fries and juice make up 25% and 40% of children’s vegetable and fruit intake, respectively. In fact, social factors such as living in food deserts or having access to playgrounds are more frequent predictors of risk of overweight and obesity than metabolic disorders. More importantly, there are numerous biopsychosocial risk factors for childhood obesity that should be considered when a patient presents with a high BMI. (see graphic below)

Addressing childhood obesity

In addressing childhood obesity, it’s essential to view the team of patient, providers, and parents as a treatment alliance. Integrating the parents and family into efforts can drastically increase the chances of success. Actively engaging the family often leads to better treatment engagement, improved family relationships, and a more consistent diet. Family involvement may prove difficult to achieve though, especially if care teams do not account for these common barriers:

- Parental defensiveness

- Time/resource constraints

- Negative communication patterns

- Additional caregivers

- Changes in relational dynamics

- Social/economic challenges

As the care team works to improve the patient’s health, it is also important to practice cultural sensitivity. Cultural differences, especially in a nation ever increasing in diversity, can be easily forgotten in conversations about health. Failing to be cognizant of these can make an already difficult message harder to swallow and less likely to resonate. Disparities such as access to safe play spaces, available food sources, values about weight, social expectations about food, and time conflicts and obligations can all drive a wedge between caring, well-meaning providers and families with different cultural norms and expectations.

Finally, messaging healthy eating and lifestyle choices to patients and their families should focus on specific, sustainable habits broken into manageable changes. Providers should move beyond soundbites like, “Eat less and move more,” to help patients identify specific actions they can realistically implement, like swapping out french fries for baked sweet potatoes or greens.

Advocating for patients struggling with childhood obesity can be tricky. The care teams who successfully navigate these challenges, however, can make a lasting impact on patients and their families.