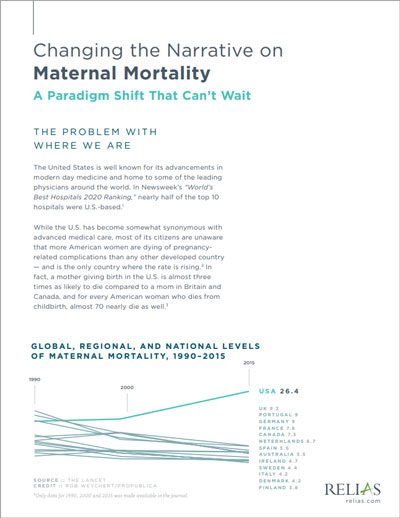

It is widely recognized that higher maternal mortality rates have persisted in the U.S. compared to other high-income countries over the last two decades. In 2017, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported that the U.S. was one of only two countries to see a significant increase in maternal mortality since 2000. Recent research and reporting indicate that maternal mortality prevention depends on simultaneously addressing three overlapping areas — clinical, social, and behavioral.

Improvements in clinical care, including better maternity care practices and OB safety protocols, have brought significant decreases in maternal mortality and morbidity worldwide. But in many countries including the U.S., social inequalities and maternal mental health have not been addressed to the same extent. Focusing on these areas will lead to improvement.

Even though many U.S. mothers have access to a very high standard of clinical care, social factors prevent many others from accessing even the minimum level of care they need. In some cases, mothers living just a few miles away from each other can have vastly different health outcomes due to variables such as income, education, race, and access to care.

Additionally, mental health conditions that previously might not have been screened for or reported (or not reported as pregnancy-related) can cause patients to slip through the cracks and lead to maternal illness and death.

Clinical improvements have raised the bar for maternity care

Undisputedly, the quality of maternity care in the U.S. and nearly every other country has increased substantially since the WHO began tracking data on maternal health outcomes. A groundbreaking 2006 article in The Lancet looked comprehensively at the “who, when, where, and why” of those most affected by maternal mortality and documented significant improvements in maternal mortality prevention around the globe.

Major clinical obstetric risks

The Lancet article detailed statistics for the major clinical obstetric risks — maternal hemorrhage, hypertensive diseases, infection/sepsis, obstructed labor, abortion, and other direct causes of maternal mortality. The data included cases occurring between the third trimester and up to 42 days postpartum. More recent studies have extended the time period to include complications occurring up to one year postpartum, which provides a more accurate picture of maternal health outcomes.

Better clinical care worldwide has come from greater availability of care, more and better-trained care professionals in the field, improved care techniques, less restrictive abortion laws, and better family planning services.

Indirect causes of maternal deaths

In the Lancet article, the authors included a maternal mortality category called “indirect causes,” which acknowledged comorbidities that contributed to mortality rates but were difficult to quantify. Much of their reporting on indirect causes focused on diseases such as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and anemia in pregnant women — not behavioral or social factors.

Yet they stated that “deaths from accidents, murders, or suicides while a woman is pregnant or within 42 days of delivery have long been classified as being incidental to the pregnant state, and thus excluded from maternal mortality statistics. However, mounting evidence suggests that such deaths might, at least in part, be caused by the pregnancy.” The study suggested that domestic violence and suicide could account for large numbers of maternal deaths in some countries, but their findings were inconclusive.

As it turns out, a deeper look at additional causes of maternal mortality helps explain why a higher-income country like the U.S. experiences alarming disparities.

Mental health often overlooked in maternal mortality prevention

In countries where clinical risks represented a high proportion of maternal deaths, obstetrical care improvements have drastically reduced maternal mortality. For example, maternal death rates dropped by over 50% in Thailand, Malaysia, and Sri Lanka over a span of 40 years due to improvements in clinical education and practices.

However, more recently in countries such as the U.S. where the many causes of rising maternal mortality have proven harder to pinpoint, the problem may be less about providers’ ability to decrease clinical risk than looking at patient health more holistically, with an emphasis on behavioral health factors. The quality of care available may be high, but access to care (and the right types of care) may be the larger issue.

Lora Sparkman, MHA, RN, BSN, Partner, Clinical Solutions at Relias, has dedicated much of her career to bringing maternal mental health issues into the spotlight. With professional and personal experience relating to both clinical and behavioral peripartum risks, Sparkman has worked to highlight the lack of focus on the intersection of maternal mortality and mental health.

Sparkman cites the necessity of using evidence-based recommended screening tools and advocates for awareness and assessment of both social and mental health issues. Too often, these types of assessments do not occur, leading to potentially tragic yet often completely avoidable outcomes.

“We should proactively identify maternal mental health risk factors using evidence-based tools like the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale or the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) so that patients can get the appropriate diagnosis and treatment they may critically need,” Sparkman said.

Social inequities may pose the gravest threat to maternal health

Regardless of whether complications affect mothers’ physical or mental health, social inequities often have the greatest impact on health outcomes. All countries — whether low- or high-income — have inequities that result in maternal deaths.

Reducing the number of these deaths can be difficult due to social determinants that healthcare providers cannot easily control. The Lancet concluded that “irrespective of the stage of development or the condition of the [country’s] health system, inequalities in the risk of maternal death are found everywhere.”

Region and income

Differences can manifest in both rural and urban areas. Rural areas may have less access to care and fewer providers with adequate education in obstetric care and peripartum health. Pockets within urban areas may also struggle with access to care, lack of education, and financial limitations.

Researchers have long established a correlation between poverty and maternal health. More recent data have revealed a wide range of effects on maternal health from economic disparities — both immediate and long-term, physical and mental.

Race and family status

Race and family status (such as marital status or the support of other family members) can also affect maternal health outcomes, even when income is not an issue. In the U.S., high-profile Black women such as top athletes Serena Williams and Tori Bowie suffered from pregnancy complications that arguably could have been prevented, with Bowie losing her life in June to respiratory distress and eclampsia.

The maternal mortality of Black women in the U.S. spiked to 69.9 per 100,000 live births in 2021, nearly triple the rate of white women. And overall, the U.S. rate was more than ten times that of Australia, Austria, Israel, Japan and Spain, which all had rates between two and three deaths per 100,000 in 2020, according to NPR.

How do we move forward with maternal mortality prevention?

Efforts such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Perinatal Quality Collaboratives are working to improve quality care for mothers and babies, with an emphasis on improving health equity — meaning providing access to care to more mothers. Stated goals include reducing premature deliveries, infections, and severe pregnancy complications.

More recently, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued its Maternity Care Action Plan, which also focuses on improving maternal health outcomes and advancing health equity. The CMS plan builds on previous ongoing efforts to expand coverage, access to care, and quality of care, as well as provide healthcare workforce support and social support for patients.

Separately, the CMS’ transition to value-based payment models provides incentives for providers to change the way they treat their larger patient communities. Value-based care will encourage providers to initiate more preventative care for all their patients and reward providers for improved aggregate health outcomes.

Continuing to increase education and awareness

Healthcare systems and providers must grapple with societal issues that challenge their ability to provide quality care to everyone who needs it. However, the continued push for improvement from medical entities, government agencies, and private organizations can only help.

Awareness and education about all three areas that require maternal mortality prevention efforts — clinical, behavioral, and social — can give providers the knowledge they need to identify gaps in care when they observe or encounter them in their practice. To target and serve previously neglected communities, prevent patterns from repeating, and stop the downward trend, it will be necessary to adopt new interventions.

Implementing recommended protocols, for example, for screening mothers for behavioral health concerns before they become serious complications can improve care and save lives. And working to partner with social support resources, connections within the community, and alternate care models such as professional midwifery can help provide access to care for those who need it most.

Changing the Narrative on Maternal Mortality: A Paradigm Shift That Can’t Wait

Do your providers and clinicians have education on the social determinants of health? Learn more about how social determinants impact maternity care.

Download now →