High Reliability in Healthcare

The Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality (AHRQ) credits high reliability organizations with cultivating resilience by relentlessly prioritizing safety over other performance pressures. A common example provided comes from the airline industry—and that despite significant pressures with aircrafts taking off and landing nearly every minute, constantly changing weather conditions, and hierarchical organizational structure, all personnel consistently prioritize safety and have both the authority and the responsibility to make real-time operational adjustments to prioritize safety.

The healthcare industry is similar with its ever-changing, fast-paced, high-risk environments, making the principles of high reliability extremely applicable.

Why Physician Buy-In?

However, if we follow the airline industry example above—if you don’t have the buy-in of the pilot, the system falls apart. In healthcare, the same can be said with physicians. Without understanding the role of physician buy-in, healthcare organizations will face major challenges launching their journey to high reliability.

Without understanding the role of physician buy-in, healthcare organizations will face major challenges launching their journey to high reliability.

Traditionally, physicians are highly competitive—a characteristic further instilled through education and training. Unlike nurses, physicians typically don’t receive heavy team-based training. That being said, physicians recognize that the traditional hierarchy model is not desirable—that individuals can make mistakes and have “off” days, and with complex systems, relying on one individual brings an inherent fraud with vulnerability. While physicians understand that a hierarchical model is not ideal, they often need to be reminded of the value in a truly team-based approach and that everyone can benefit from the overall management of the care delivered to patients.

Physician buy-in comes from knowing that physicians have a team that shares the same knowledge to manage patients in their absence when they’re not in the office, on the floor, etc. Physicians will see value in putting systems in place that benefit the team, the hospital—and above all—the patients. This support and trust from physicians empowers the team, ultimately letting them know that they’re valued.

Culturally, there’s been an improvement in the physician approach to relinquish the hierarchy model and favor one that looks towards teams. For a physician reluctant to change, obtaining their buy-in can be difficult, but will almost always be the most beneficial. Effectively recruiting these physicians as “champions” will go a long way in supporting the organization’s high reliability journey.

The 5 Characteristics of High Reliability

Below are a few examples of how physicians play a role in the high reliability journey, as outlined by the five characteristics of high reliability:

1) Preoccupation with failure

When obstetric adverse events occur, nurses and physicians often personalize what went wrong, creating self-blame and falling back on a common reflex to argue around the event. The key premise of preoccupation with failure is to recognize that the outcomes are not ideal, look at the process and systems to define why it occurred, and look for opportunities to avoid similar events in the future. The focus should be on assessing opportunity for improvement without solely focusing on one individual’s actions/mistakes. Physicians can often set the example to look to the “what” (systems and processes) vs. the “who” (healthcare workers).

2) Reluctance to simplify

Healthcare environments are undoubtedly complex—multiple people are performing multiple tasks, leading to an increased risk of errors. When adverse events occur, root cause analyses (RCAs) are a useful tool to break down the complexity that’s inherent in medicine. The RCA is effective in giving proof to how complex critical care algorithms truly are, creating an appreciation for the complexity of the situation. RCAs force us to consider a broad, expanded view of the care delivery systems and processes, and prevent resorting to shortcuts without first considering other potential factors that may be involved. In fact—physicians often quote a common anecdote that, “one of the worst things we can do for a patient is to make a diagnosis.” Diagnoses can lead to labeling, and a siloed approach to care. With a reluctance to simplify, a differential diagnosis can be maintained—keeping a broad scope without overlooking possible approaches to care that may have a greater impact on the patient.

3) Sensitivity to operations

Care settings will usually include different disciplines, and often multiple teams. It’s important to remember that the sum of the parts is greater than any individual team member and recognize the complex environment for what it is. Many associates impacting a patient’s care may never even have direct contact with the patient, but that should never mean they’re overlooked. Considering the “teams beyond your team” approach helps physicians to consider other roles in the healthcare environment, such as housekeeping, which plays a major role in the mother’s delivery and postpartum care. The engagement from these teams is equally important as the frontline caregivers’.

4) Deference to expertise

In labor and delivery it’s especially common for team members to assume that physicians “have all the answers.” In reality, one person is never the ultimate holder of the best information. It’s important to recognize that nurses are often more engrained in the hospital and state regulations, and certain nurses within the team will have more knowledge and experience than others. Other times, a recent graduate nurse’s fresh perspective may bring something new to the table. Each nurse has certain expertise and should be made to feel comfortable speaking up and sharing concerns. Looking outside of the direct labor and delivery team, physicians often rely on the expertise of care team members in other departments (i.e., working with the blood bank when treating a postpartum hemorrhage or housekeeping to speed up room turnover in the OR).

5) Commitment to resilience

During an organization’s high reliability journey, the initial hurdle is typically the adoption of change. By starting the journey with a high level of energy and emphasis on commitment, it will drive the culture shift to maintain a persistent effort to creating a culture of high reliability. There’s a natural weaning that may result in a slight rise in events, and fatigue and burnout may occur. Recognizing that this does happen—it’s important to bounce back and continue the emphasis that the journey to high reliability is an ongoing, long-standing game, but the benefits are immeasurable.

Physician buy-in and building a culture of high reliability are major components of an organization’s maternal safety improvement efforts. To learn more about how these factors can influence maternal care, download the white paper below.

Editor’s note: This post was originally published in August 2019 and has been updated with new content.

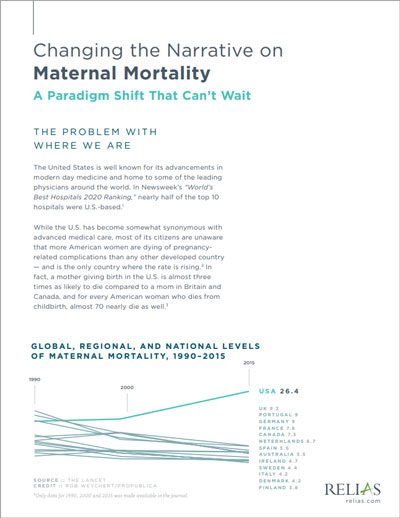

Changing the Narrative on Maternal Mortality: A Paradigm Shift That Can't Wait

The U.S. is faced with an urgent call to improve maternal care. Learn how developing a culture of high reliability can help.

Download White Paper →